Rectal prolapse refers to the collapse or "dropping" of all or part of the wall of the rectum towards the anus or on through the outside of the anus.

It's often described as a feeling of sitting on a ball after having a bowel movement, or a feeling that something's not right. While rectal prolapse shouldn't be ignored, it's not necessarily a medical emergency.

Treatment will depend on the extent of the prolapse. In some instances, it's possible to push the rectum back into place.

What Are the Types of Rectal Prolapse?

Rectal prolapse can be partial, complete, or internal. Partial prolapse (mucosal prolapse) is when the rectum slides out of place and partially protrudes from the anus. This type of prolapse is more common in younger children. Complete prolapse is when the entire wall of the rectum is displaced. Initially, the anal protrusion may only be noticeable during bowel movements before occurring more frequently. If a wall of the colon or rectum slides over another portion, it's referred to as internal prolapse (intussusception). With this type of rectal prolapse, the rectum does not protrude.

What Causes It and What Are Symptoms?

There are many factors that can contribute to rectal prolapse. Children with cystic fibrosis sometimes have rectal prolapse. Malnutrition, having had previous anal surgery, chronic infections, and straining while making bowel movements are among the other factors that may increase a child's odds of developing some type of rectal prolapse.

Adults may develop this problem if they have weak pelvic floor muscles, tissue damage related to childbirth, or issues with chronic constipation. Age-related muscle weakening may also be a contributing factor. Symptoms related to rectal prolapse include:

- Noticing an anal bulge on the exterior part of the anus

- Rectal or anal discomfort

- Rectal bleeding

- A red mass that's visual around the anal opening

- Stool leaking or blood or mucus coming out of the anus

How Is Rectal Prolapse Diagnosed?

During an initial physical exam, the strength of the anal sphincter may be checked. The anal and rectal area may be visually examined with either a sigmoidoscopy or a colonoscopy. A barium enema is sometimes done to check for ulcers, tumors, or other intestinal abnormalities. With children, a sweat test may be performed to check for cystic fibrosis.

What Are Treatment Options?

In children, rectal prolapse often goes away with little or no intervention. It may be helpful for parents to use a special potty-training toilet to minimize instances of straining during bowel movements. Adults may benefit from Kegel exercises to control rectal prolapse by strengthening pelvic floor muscles. Dietary changes may also be recommended to reduce issues with constipation.

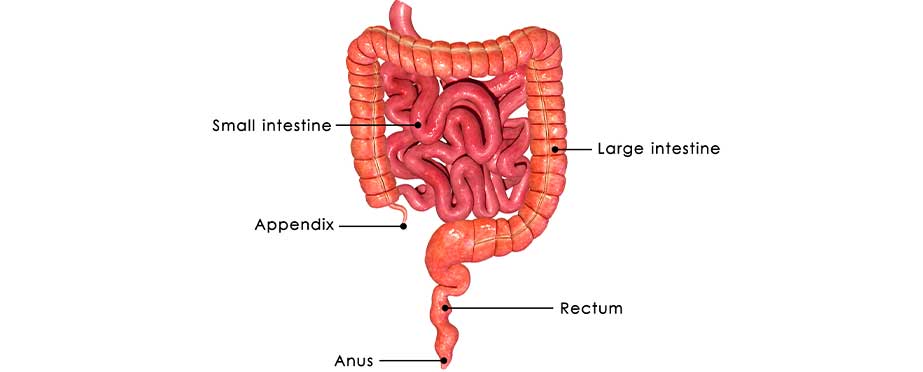

If initial treatment efforts for rectal prolapse aren't effective, surgery is usually the only option. The most common procedure involves attaching the rectum to pelvic floor muscles or the sacrum – the lower part of the spine. Another possibility is to remove part of the large intestine that's not supported by adjacent tissues. Both procedures are sometimes performed at the same time.

Rectal prolapse isn't always preventable, especially if it's caused, in part, by an existing biological defect. But the risk of developing a serious issue with a misplaced rectum may be minimized by taking steps to avoid constipation as much as possible. This usually means eating more fiber-rich foods, drinking more water, and maintaining a healthy weight.